Some events teach you facts. Others make you wish you had been there sooner. ‘Wetlands after Dusk’ at Beddagana Wetland Park did both. It was designed to help people understand the science, yes – but also to feel how alive, complex, and quietly busy a wetland really is.

Starting with Water: The Foundation of It All

The session opened with a short introduction by Narmadha Dangampola, and then we moved straight into action. A water quality testing demonstration took place alongside a mini clean-up, setting a simple but powerful message: if we want to understand ecosystems, we also have to care for them.

Participants learned what pH really means (beyond textbook definitions), how oxygen and carbon dioxide levels naturally change between day and night, and why temperature shifts matter so much for aquatic life. The science was explained in a way that made it easy to connect the dots.

One moment that caught everyone’s attention was the explanation of the ferrous oxide phenomenon – that rusty-looking layer sometimes seen floating on wetland water. Instead of being brushed off as ‘pollution’, it was explained as a chemical process shaped by wetland conditions. We also learned how plants, microbes, and animals constantly change water quality, reminding us that wetlands are not still or silent, they are always at work.

Birds That Tell Time and Guard Territory

As evening approached, the wetland slowly introduced its winged residents. Participants were guided through sightings and stories of nocturnal and migratory birds, including the Indian Pitta – popularly called the “6 o’clock bird”, the White-bellied Drongo, Brown Hawk Owl, Indian Nightjar, Jerdon’s Nightjar, Common Hawk Cuckoo, Black-crowned night Heron, and Whistling Duck.

What made this session special wasn’t just naming species, but understanding behaviour. For instance, learning that the Indian pitta is highly territorial because it fiercely protects insect-rich feeding areas helped people see birds not just as visitors, but as active managers of their own ecosystems.

The Small Creatures Doing Big Work

Next came a topic many don’t usually associate with wetlands – small mammals. Prof. Saminda Fernando, a Professor of Zoology, explained their crucial role in seed dispersal and ecosystem balance. He walked participants through how animals are studied ethically using live traps such as Sherman traps, Longworth traps, pitfall traps, and mesh or cage traps.

Did you know? small mammals are generally defined as animals weighing under 500 grams.

Frogs: The Wetland’s Early Warning System

If there was one moment where people truly leaned in, it was during the amphibian session by Sanoj Wijayasekara. Frog calls filled the night as he played recordings and demonstrated how these sounds are captured and analysed using specialised software.

What stayed with many participants was the idea that frogs respond to environmental change at a micro-habitat level. Long before humans notice a problem, frogs are already reacting. Suddenly, their calls felt less like background noise and more like important messages.

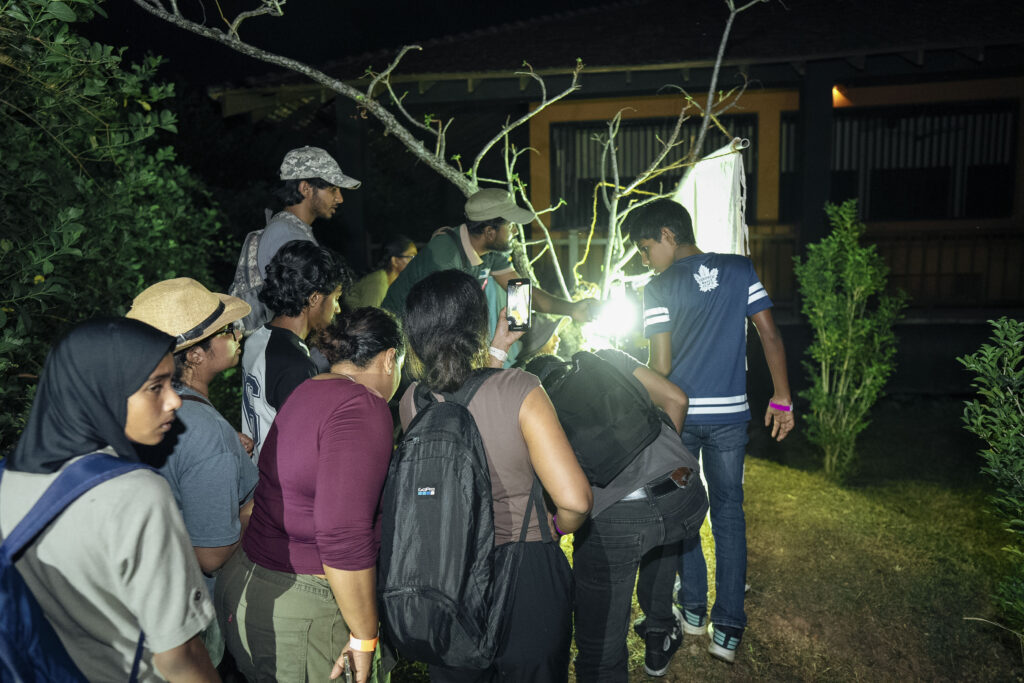

Moths, Light, and Subtle Signs of Change

Under a simple white sheet and artificial light, Nuwan Jayawardene, a Lepidoptera expert, revealed a surprisingly rich world of moths. He explained that moth observation is completely non-lethal, the insects are never touched.

Participants were intrigued to learn that rising pollution and darker environments are linked to an increase in brown-coloured moth species. Even more impactful was hearing that this research feeds directly into reviews for Sri Lanka’s National Red List, showing how quiet fieldwork can influence national conservation decisions.

Bats: Misunderstood, But Essential

The bat session by Dr. Tharaka Kusuminda, a bat biologist, changed a few minds that evening. He explained why bats evolved to roost upside down, how complex their social and mating calls are, and why they play such an important role in controlling insect populations.

Participants were also introduced to safe research methods like mist netting and harp netting, giving insight into how science is done responsibly.

Carnivores, Conflict, and Coexistence

The conversation talks then moved to larger mammals. Sethil Muhandiram, Leopard Conservationist, spoke about leopard behaviour, breaking down common fears. Learning that leopards usually do not attack standing humans, but may react to crouching, prey-like behaviour.

Camera trapping was introduced as a non-invasive research tool, with details on placement, distance, and even why researchers wear gloves to avoid leaving scent. Participants also learned that there are eight leopard subspecies worldwide, and that the Sri Lankan leopard is the largest, confirmed through DNA research by Dr. Sriyanie Miththapala.

Adding another layer, Ashan Thudugala, Carnivore Conservationist, shared insights into fishing cat research, highlighting how wetlands are essential for the survival of this elusive species.

Ending the Night Where Learning Began

The Wetland Night Walk brought everything together. By then, participants weren’t just observing, they were noticing patterns, listening differently, and asking better questions. The wetland felt less like a park and more like a classroom without walls.

Why This Event Truly Worked

What made this event successful was not just the expertise in the room, but how that knowledge was shared clearly, and patiently. The science was understandable, the learning felt exciting, and the experience left many thinking, “I don’t want to miss the next one.”

The overwhelmingly positive feedback confirmed this. For Dilmah Conservation, the evening reinforced something important: when people are given the chance to experience nature this closely, curiosity turns into care. And that’s exactly why more events like this matter, not just for learning, but for building lasting connections between people and the ecosystems that support them.